Stop Treating 40+ Mothers as a Risk - They’re Driving Stability and Growth

Jan 26, 2026

By Marie-Charlotte Rouzier, guest writer.

Western societies are undergoing a demographic transformation. Fertility is falling, populations are ageing, and an increasing share of children are being born to mothers in their late thirties and forties. This shift is often framed in terms of risk or decline.

But that framing misses the opportunity.

Later motherhood is emerging as a meaningful part of how our societies - and our economies - sustain themselves. It brings new forms of stability, clarity, and competence into family-building. And as parental rights expand and organisations rethink how they support working parents, a more hopeful picture is taking shape.

We’re not facing a crisis story. We’re seeing the opening of a new chapter - one where women build families and careers on timelines that finally reflect real life.

1. The demographic backdrop: low fertility, ageing societies, later births

Across OECD countries, the average total fertility rate has more than halved, from about 3.3 children per woman in 1960 to around 1.5 in 2022 – well below the 2.1 replacement level typically needed to keep populations stable.

In the EU, the total fertility rate stood at 1.38 births per woman in 2023, with many countries now in the “ultra-low” fertility range below 1.4.

At the same time, births are shifting to later ages:

- In the EU, the share of live births to mothers aged 40 and over has more than doubled in twenty years – from about 2.5% in 2002 to 6.0% in 2022.

- In many member states, the average age at first birth is now close to, or above, 30.

- OECD data now shows that fertility rates for women aged 40–44 have surpassed adolescent fertility rates – a complete inversion of historical patterns.

In parallel, life expectancy has increased and populations are ageing rapidly, with OECD and EU reports warning of long-term pressure on labour markets, welfare systems and public finances if these trends continue.

In other words: Western societies need more children, yet many of those children are now being born to older parents – especially older mothers.

Late motherhood is not a marginal phenomenon. It is part of how our societies are reproducing themselves.

2. The legal and cultural landscape: rights catching up, slowly

The law has started to recognise that caregiving is not a private hobby but a structural pillar of the economy.

In the EU, the Work-Life Balance Directive (2019/1158) sets minimum standards for:

- paternity leave,

- parental leave for both parents,

- carers’ leave,

- and the right to request flexible working arrangements for parents and carers.

Recent assessments of its implementation show gradual progress: more countries introducing or upgrading paid paternity leave, strengthening parental leave schemes, and embedding flexible work in law rather than leaving it to employer goodwill.

Beyond the EU, similar trends appear:

– extended parental leave,

– more equal sharing between mothers and fathers,

– and more explicit protection against discrimination linked to pregnancy and parenthood.

However, two gaps remain:

- These rights are often designed around a “standard” parent in their late 20s or early 30s, not around the reality of first-time or returning mothers at 38, 42, or 45.

- Cultural norms lag behind legal texts. Policies may change, but stigma around “starting too late” or “having a baby at your age” still circulates in workplaces and even in healthcare.

So the legal architecture is improving. The lived experience is not always aligned.

3. Medicine: up-to-date science, outdated framing

Clinically, it is true that pregnancy after 35 and after 40 is associated with statistically higher rates of certain complications – gestational diabetes, hypertension, caesarean section, some neonatal risks. Large reviews continue to document these patterns.

But how we talk about those risks matters.

The age threshold of 35 – used since the mid-20th century to define “advanced maternal age” – is a historical artefact as much as a biological boundary. It emerged at a time when very few women had children after 35, and when genetic testing and obstetric care were far less advanced than today.

Several problems now coexist:

- The vocabulary: terms like “geriatric pregnancy” are increasingly criticised by patients and clinicians as stigmatising and obsolete, with professional bodies and surveys calling for their retirement.

- The framing: women over 35 or 40 often report that their pregnancies are discussed primarily through the lens of deficit and danger rather than personalised, evidence-based care.

- The psychological impact: research on age-based stereotype threat in reproductive healthcare has shown that being repeatedly labelled “old” or “high risk” can itself increase stress and harm prenatal mental health.

The science is not the issue. We should absolutely acknowledge and monitor the additional medical risks.

The issue is the narrative: Older pregnant women are too often treated as problems to be managed, rather than as competent adults making informed decisions within complex personal, professional, and demographic realities.

In an era where 40+ motherhood is becoming structurally significant for ageing societies, this narrative is no longer fit for purpose.

4. Late motherhood as strength, not anomaly

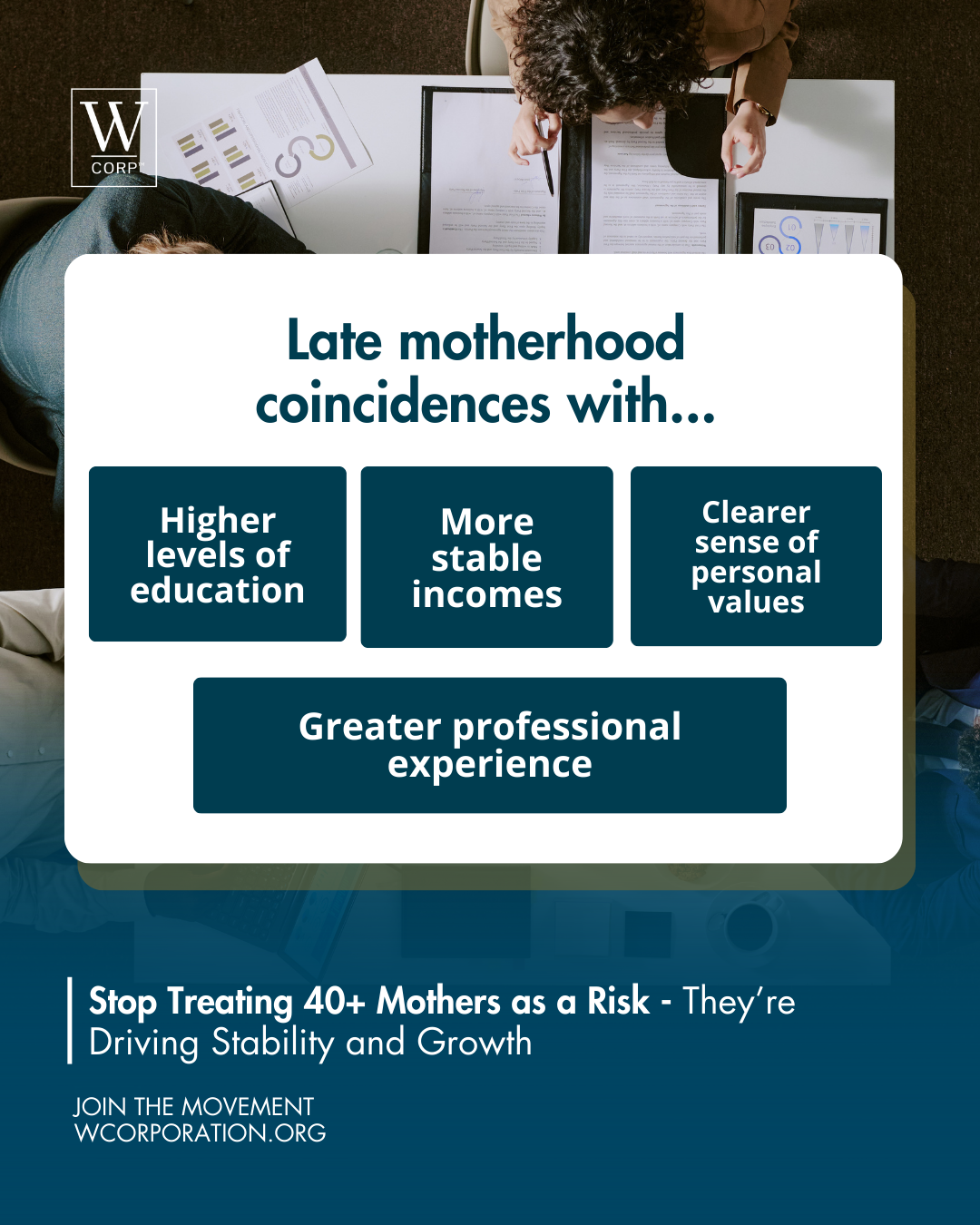

When we look beyond the risk tables, late motherhood often coincides with:

- Higher levels of education.

- More stable incomes.

- Greater professional experience.

- Clearer sense of personal values and boundaries.

OECD work on “women, work and the population puzzle” has highlighted that enabling women to combine sustained employment and motherhood is central to addressing low fertility and population ageing – not a side issue.

In this context, women who become mothers later in life bring a specific set of strengths:

- Economic stability: they are more likely to be established in their careers. • Leadership skills: years of managing teams, projects and crises translate into sophisticated caregiving and decision-making.

- Clarity: the choice to pursue motherhood at 40+ is rarely accidental; it is often the product of deep reflection and deliberate trade-offs.

Yet our dominant story remains: “You are late. You are risky. You are a warning.”

We need a different story: “You are part of how our societies continue. You bring assets, not just risks. And you deserve systems designed with your reality in mind.”

5. What organisations can (and should) do

If demographic decline, ageing populations, and later motherhood are structural trends, then employers are not bystanders. They are part of the solution.

Concretely, organisations can:

- Normalise pregnancy at every adult age.

Treat a pregnancy at 42 as a normal scenario in HR policies and manager training, not an awkward exception.

- Design flexible work as default, not favour.

Align with the spirit of the Work-Life Balance Directive: genuine flexibility in hours, location and workload for parents and carers – including senior staff. 3. Equalise parental leave across genders and roles.

The more men take substantial leave and flexible work, the less late motherhood is penalised in practice and perception.

- Protect careers during fertility and pregnancy journeys.

Clear non-discrimination commitments around fertility treatment, pregnancy loss, high-risk pregnancies and return-to-work, with pathways back into progression.

- Train leaders on bias around age and motherhood.

Not just gender bias, but age-and-motherhood bias: the subtle idea that a 40+ pregnant leader is “unstable”, “about to slow down”, or “less committed”.

6. Collect data and listen.

Anonymous surveys, listening sessions, and ERGs to understand how policies land for parents at different ages – and adjust accordingly.

Late motherhood is not going away. If anything, trends suggest it will become more visible as cohorts who delayed childbearing move through their 40s.

To conclude

The demographic data is unambiguous: parents are older, populations are shifting, and the timing of family life is changing. But alongside this, law, policy and workplace culture are gradually adapting. Parental rights are stronger. Flexible work is more widely accepted. And forward-looking organisations are redesigning roles with human complexity in mind.

These changes don’t signal decline. They signal evolution.

Later motherhood isn’t an outlier or an anomaly. It’s part of a broader movement toward more deliberate, more stable, more empowered family-building - a movement aligned with the needs of modern economies.

If organisations lean into this reality, they don’t just support their people. They invest in the resilience of the future workforce.

And for women who choose to build families later in life, this moment offers something previous generations rarely had: the legitimacy to do so with pride, without apology, and with systems increasingly designed to support them.

This isn’t a story of risk. It’s a story of possibility.

Marie-Charlotte Rouzier

https://www.linkedin.com/in/mariecharlotter/

Marie-Charlotte Rouzier is a strategist and researcher with a career shaped by international mobility, structural change, and lived complexity. She has lived and worked across several countries, including Tunisia, Hungary, Australia, the United Kingdom and France, building experience across technology, finance, innovation ecosystems and education, often at moments of institutional or organisational transition.

Alongside her professional trajectory, she has navigated major personal chapters: returning home after years abroad, becoming a mother later in life, experiencing single motherhood, rebuilding family life, and continuing to operate in demanding professional environments. These experiences inform a distinctive perspective on leadership, work, care, and resilience — grounded in practice rather than abstraction.

More recently, her work has centred on strategic research, ecosystem engagement and long-form analysis within the UK SME and innovation landscape, where she operates at the interface of policy, data and real-world decision-making. She contributes to evidence-led discussions on demographic change, work models and organisational design, bringing together analytical rigour and lived insight to illuminate how systems perform under pressure.

References

- OECD – Family Database

https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

- OECD – Women, Work and the Population Puzzle

https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/women-work-and-the-population puzzle_5e2e6aae-en.html

- Eurostat – Fertility Statistics

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics

explained/index.php?title=Fertility_statistics

Marie-Charlotte Rouzier Dec 2025 5

- United Nations – World Population Prospects

https://population.un.org/wpp/

- European Union – Work-Life Balance Directive (EU) 2019/1158 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019L1158 6. OECD – Paid parental leave

https://www.oecd.org/en/blogs/2023/01/Paid-parental-leave--Big-differences for-mothers-and-fathers.html

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/obstetric-care consensus/articles/2022/08/pregnancy-at-age-35-years-or-older